Variation on a form

In what form does Mulier’s material come into existence? The material appearance determines its content. Anyway, that’s how it is supposed to be in visual arts. Visual language differs chiefly from spoken language in making material, form and content coincide. And these three form an inextricable entity, reinforcing each other continually.

A classic example is "The sisters of the illusion" by Victor Rousseau (1865-1942). Three naked ladies are meticulously cut out of a veined white marble block. The ideal of beauty of that time; a (preferably) blue-veined fair skin coincides naturally with this material. Both enhance the illusion. Art is illusion.

These lines follow on my meeting with Wouter at his place in the charming Pieter Coutereelstreet. I visited the artist’s workshop and his study. We had a cup of coffee and played with the tame rabbit.

I’m looking at the sculpture of Wouter Mulier and writing this text on the eve of my participation in the Brussels Marathon.

To dwell in the presence of art is the ideal method to forget the long competition. There is a special kind of kinship between the sensation of a marathon and the experience of Mulier’s sculpture. Both carry a different interpretation of time than that of the social hic et nunc. Both reinvent as it were time and space.

Vogelboom (1999, Birdtree) on Square De Groef in Leuven, Overvloed (2000, Abundance) in Hasselt and Variation on a form (2004) call in question the social space. Questioning things takes time.

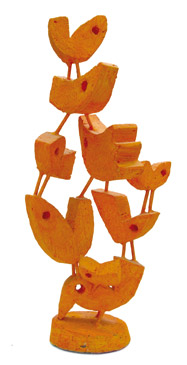

Model Bird tree: 1999,

polystyrene, copper wire (26/12/8 cm)

Bird Tree: 1999,

powder coated steel (350/150/150 cm)

Variation on a form

In what form does Mulier’s material come into existence? The material appearance determines its content. Anyway, that’s how it is supposed to be in visual arts. Visual language differs chiefly from spoken language in making material, form and content coincide. And these three form an inextricable entity, reinforcing each other continually.

A classic example is "The sisters of the illusion" by Victor Rousseau (1865-1942). Three naked ladies are meticulously cut out of a veined white marble block. The ideal of beauty of that time; a (preferably) blue-veined fair skin coincides naturally with this material. Both enhance the illusion. Art is illusion.

These lines follow on my meeting with Wouter at his place in the charming Pieter Coutereelstreet. I visited the artist’s workshop and his study. We had a cup of coffee and played with the tame rabbit.

I’m looking at the sculpture of Wouter Mulier and writing this text on the eve of my participation in the Brussels Marathon.

To dwell in the presence of art is the ideal method to forget the long competition. There is a special kind of kinship between the sensation of a marathon and the experience of Mulier’s sculpture. Both carry a different interpretation of time than that of the social hic et nunc. Both reinvent as it were time and space.

Vogelboom (1999, Birdtree) on Square De Groef in Leuven, Overvloed (2000, Abundance) in Hasselt and Variation on a form (2004) call in question the social space. Questioning things takes time.

Model Bird tree: 1999,

polystyrene, copper wire (26/12/8 cm)

Bird Tree: 1999,

powder coated steel (350/150/150 cm)

His work as an outlined object in space...

I like to divide Western-European artists, all along the history of art in, on the one hand, those artists for which line/relation prevail, on the other hand, the colourists. Mulier belongs to the first group. He doesn’t care all that much for light and colour sensation. He is fascinated by the presence of the outlined object in a larger space. Only there does his production process come to a halt.

The power of Mulier’s visual language lies in the experience of the three-dimensional reality.

The spectator is stimulated to see the broad outlines and not to get involved in side issues. This art urges one to cast a look at the essence of reality. The work of Mulier stimulates a feeling of synthesis while being looked at. It is as if for an instant everything falls into place. This harmony lasts as long as the onlooker looses himself in total perception.

A few works of Mulier are called ‘Variation on a form’. I find this title very much to the point. That’s why I have used it as a heading for this text. Over and over again Mulier is looking for his ultimate expression of reality. Each work becomes a variation on this fundamental drive. Each work clearly bears the stamp of Mulier. “Mulier hoc fecit” is superfluous.

This makes me think of the words on one of Paul Gauguin’s paintings: "Where do we come from? What are we? Where do we go?"

model Spring-tide: 2005

wrought iron (21/18/20 cm)

The relation form-technique

The sculptures of Mulier contain an apparent paradox. At first sight the work seems to have been shaped industrially. A second sight quickly shows that this object is not just a bent piece of iron. It is a subjective product that has been folded laboriously, cut, sanded and folded again. The path to appearance in real space is toilsome. The idea is 1% of a total work of art. The remaining 99% are the result of discipline, training and hard work.

In spite of the purity of their form, Mulier’s sculptures are very physical. The artist buys a sheet of 316/L stainless steel and with a minimum of tools he works and manipulates the material. Mulier is a manipulator. He bends the material to his will. He shows his line. His visual, spiritual, and conceptual freedom is restricted by his physical limits: the object only folds as far as the reach of his arms. Man as the measure of things. The object becomes subject. The 316/L stainless steel becomes a Mulier form: a variation on a form.

The spectator’s experience of space

Mulier cares about the spectator. During the exhibition ‘Landshapes’ in Leuven, enlarged graphic reproductions or drafts are being projected on the walls of the exhibition hall. Three dimensions are turned into magnified two dimensions. I quote the artist:

"In attachment I have included some ‘projections’. They are graphic reproductions of figures or small drafts which I’ll have enlarged and applied on the walls of the exhibition hall in Tweebronnen. In playing with the size, the point of view (bird’s eye view, view from below) and the possibility of recognition (the ‘real objects’ are present in the exhibition) we want to encourage people to look more actively and to experience space more intensely."

This quote illustrates how important observation is for Mulier. He puts ‘real objects’ between inverted commas. Of course, the projections are also real objects, but in the combination of both, we ‘see’ the specificity of the ‘form’ (2D or 3D) and of the material (projection on the wall or steel). Both are different but refer to one another. This way Mulier wants the visitor to experience the sensation of space more intensely.

Where am I? What am I? Who am I?

In this context I’d like to jump to Yves Klein’s “Saut dans le vide” (video 1960) and to one of his poems where he wrote: "Space that waits for our love, as I wait for you every day: come with me into space".

Aspects of his work on the basis of concrete examples

When we look at Mulier’s sculptures, we are invited to a round trip. These objects possess space, or in other words, they absorb and transform space, giving it a more open character. The anecdotal character of social space is minimized. Reality is essentialized.

This is no minimal but essential sculpture. The parameters are: volume, perspective, gravity, lightness, movement, development

What strikes one, is that the volume of space that is conjured up, does not follow the size of the sculpture. The picture of Schicht (Flash, 2004) illustrates this: from a large distance you can see that Schicht takes in space, and gives it back purified. This sounds like science-fiction. Of course this concerns the illusion of art, the magic of the figure.

Or as Magritte says: "A sculpture is no work of art but a figure that has to contribute to the emancipation of the spirit."

Schicht, 2004, stainless steel (95/100/47 cm)

From nearby, the figures grow larger but the space narrows.

What is essential in this discourse is the relation of the observer with the sculpture. In fact, a relation is, thinking of Arthur Schopenhauer, a failed unity.

In Schicht (Flash, 2004) you can loose the here and now, your subjectivity, and be absorbed in an essential line pattern. Surfaces are staggered, become narrower, broaden, the perspective changes constantly. Schicht puts us continually on the wrong track. The next step would be: Newton’s apple falling upwards.

Speaking about apples. In Wouter’s garden I saw a successful copy of ‘The temptation of Eve’ (ca. 1130, Musée Rolin in Autun) by the Romanesque sculptor Gislebertus. From history of art I remember that this sculptor was one of the first to sign "his" sculpture. I like to connect "Gislebertus hoc fecit" (made by Gislebertus) with Gauguin’s vital question: "Where am I?". Gislebertus takes position in space: here I ‘am’

The temptation of Eve (Evan van Autun), 1988, petit granit (40/75/15 cm)

During a training in stone carving Mulier chose this work as a project. It focuses on ‘The temptation of Eve’ at the very moment of original sin. Eve had to bite in the apple. Only this way could she leave behind her paradisiacal constitution and lose herself in time and space.

This scene is about the sensory experience of space and about biting in the here and now. Mulier nourishes this original sensual perception.

I am very charmed by Gislebertus’s line pattern. Mulier’s copy shows us the importance of the direct contact with the figure in its concrete environment. I would like to speak in this respect about visual tactility. It is the last factor, next to material, form and content in Wouter’s art. Eve is embraced by sculpted and real ivy. The "hortus conclusus" is complete.

Schicht is a dance of lines and surfaces. The sculpture contains a certain leitmotiv. The work of art varies round a form. Schicht stretches out but always comes back to itself: expansion and clenched power at the same time. This sculpture is not only an accumulation of slanting lines and surfaces. It is a fascinating story being told. A figure that invites to take position in space.

"... if somewhere it is true that the whole is more than the sum total of the parts, this applies to a work of art."

Overvloed, 2000, stainless steel

(225/170/60 cm)

The final setting in Hasselt attracts even more our attention to the line pattern as the financial institution behind the sculpture is exclusively built up of verticals and horizontals, which brings about a line pattern full of contrast. To the visitor of the bank who looks for a perfect ‘balance’, this must be an unexpected experience.

In fact Clustered columns II (2001) can be read as one line that staggers in space. Here the leitmotiv is the V-form, which the spectator can distinguish several times. Clustered columns II also plays with the relation of two dimensions versus three dimensions. Halfway the line opts for the third dimension. Actually, the line escapes from its rectilinear constitution and flees into space. The line opens out.

Clustered Columns II, 2001, stainless steel (300/230/110 cm)

Walking, 2006, powder coated aluminium

(180/125/80 cm)

By naming his abstract figures Mulier wants to make them more accessible. The risk of becoming anecdotic and narrowing the way one looks, lurks around the corner. The word steers always the interpretation of the figure.

I remember in the first place that Mulier cares about his sculpture and about the spectator.

He wants to draw each spectator as closely as possible into his sculptural language.

The word ‘space’ fell many times in the Pieter Coutereelstreet. All visual art is in fact space art.

Wouter told me a nice story about the singing classes of his youth. The teacher made this comment: "But please, do stand in space !". It is striking that he still remembers that recommendation.

It illustrates his fascination with space.

When I think of song and music I immediately think of dance and movement. Mulier’s figures surely are somewhat like dancers who show their amplitudos. Without time music doesn’t exist. The melody makes us aware of space of time. Likewise, the sculpture of Mulier contains space of time, and this is not only true while contemplating the figure. To absorb space and give it back, a space of time (a slowness) is also necessary.

I like to end this text with a quote of the Leuven philosopher Patricia De Martelaere… Indeed, Wouter Mulier’s work invites us to ‘contemplate’ in the same way.

"The ‘seer’ is he who enters into unity and lets his subjectivity disappear totally into the object that surrounds him-he gives up his independence entirely and waits for something to address him in a language that is not his own."

Filip Van de Velde